In Spencer, Iowa, the local hospital stands as one of the few remaining facilities offering inpatient mental health services amidst a nationwide decline. Over the past decade, nearly 100 hospitals across the U.S. have closed their psychiatric units, largely due to financial pressures. The trend raises concerns that upcoming federal budget cuts to Medicaid could further exacerbate the crisis, leading to more closures.

Spencer Hospital’s leadership insists on maintaining its 14-bed psychiatric unit, even as it incurs annual losses of $2 million. CEO Brenda Tiefenthaler reports that 40% of their psychiatric patients rely on Medicaid, far exceeding the 12% of all hospital inpatients covered by the program. Additionally, 10% of these patients are uninsured. This reliance highlights a systemic issue: Medicaid serves a disproportionate number of individuals in need of mental health care, yet hospitals struggle to stay financially viable while providing these essential services.

Medicaid currently supports approximately 72 million low-income Americans, covering a significant portion of those experiencing mental health crises. Tiefenthaler warns that if funding cuts lead to loss of coverage for these patients, many will delay seeking help until their situations worsen, resulting in more individuals arriving at emergency rooms in crisis.

While Republican leaders in Congress have pledged to protect Medicaid beneficiaries, they simultaneously support budget reductions that could impact the program. Jennifer Snow, director of government relations for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, emphasizes the critical shortage of inpatient mental health services, which has been further diminished by both private and public hospital closures.

Data from the American Hospital Association indicates that nearly 100 hospitals have shut down their inpatient mental health services in the last ten years. The financial losses associated with these services make them targets for cuts, as they often operate at a loss compared to more profitable medical specialties. Snow acknowledges the difficult choices hospitals must make to remain open, as they face the dual pressure of financial sustainability and the need to provide care to vulnerable populations.

In Iowa, the situation is particularly alarming. The state has the highest rate of mental illness among nonelderly Medicaid recipients at 51%. As of February, only 20 out of 116 community hospitals in Iowa maintained inpatient psychiatric units. The state is also home to four freestanding mental hospitals, which are insufficient to meet the demand for care. The Treatment Advocacy Center estimates that Iowa requires a minimum of 960 inpatient mental health beds, with an optimal number closer to 1,920. Currently, the state has around 760 beds available, concentrated in metropolitan areas, leading to significant wait times for treatment.

Patients often find themselves waiting for days in emergency departments, which are not equipped to provide the necessary psychiatric care. Clay County Sheriff Chris Raveling reports that deputies frequently transport individuals to distant facilities, sometimes driving several hours to find available beds. This inefficient system frequently results in individuals being held in jails for minor offenses related to their mental health issues, exacerbating their conditions without providing adequate treatment.

Jon Ulven, a psychologist working in the region, expresses concern about the long-term consequences of delayed treatment for conditions like psychosis, which often emerge in adolescence. Early intervention can significantly improve outcomes, yet access to timely care remains a challenge. Ulven cites a 2022 study showing that states that did not expand Medicaid experienced faster increases in suicide rates compared to those that did.

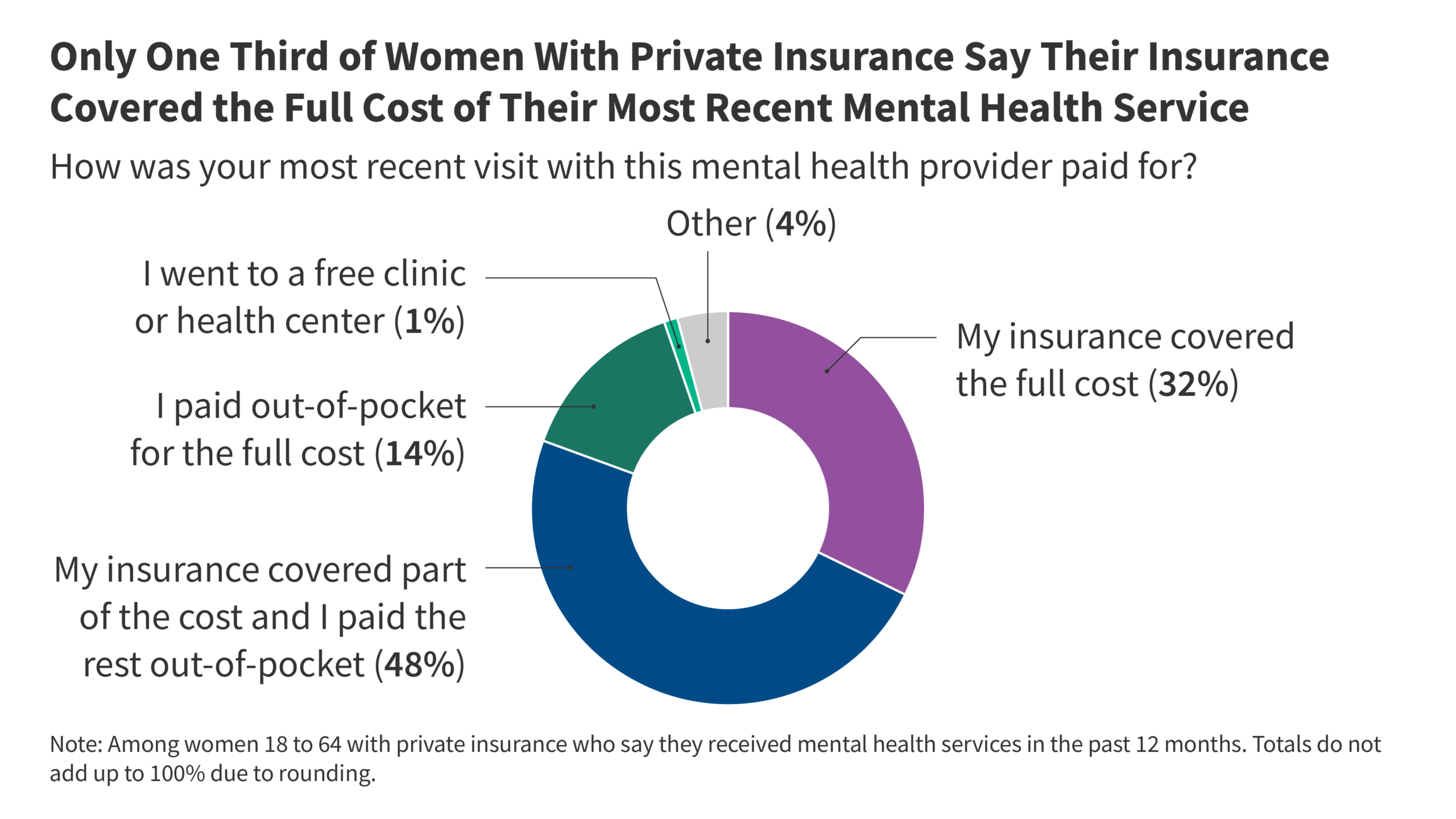

Nationally, Medicaid covers nearly 41% of psychiatric inpatients in hospitals, while its coverage for cancer and cardiac patients is much lower at 13% and 9%, respectively. If Medicaid rolls decrease, hospitals may face an influx of uninsured patients seeking urgent care, further straining resources. Steve Wasson from Strata, a financial consulting firm, notes that while Medicaid payments are lower than those from private insurance, they are better than no payment at all.

Spencer Hospital has also managed to keep its birthing unit operational, which faces similar financial challenges. The hospital employs two psychiatric nurse practitioners and two psychiatrists, including one providing remote care from North Carolina. Local resident David Jacobsen has experienced the critical need for these services firsthand, as his son Alex received support from the hospital’s mental health professionals before his tragic death by suicide in 2020. Jacobsen fears that further cuts to Medicaid will lead to additional mental health service reductions, ultimately harming those who need care the most.

The impact of service reductions extends beyond Medicaid recipients; the entire community suffers when local hospitals limit or close mental health services. Jacobsen’s family’s experience illustrates the widespread need for accessible mental health care. As one of his daughters wrote in Alex’s obituary, mental illness affects everyone and requires urgent attention and resources.