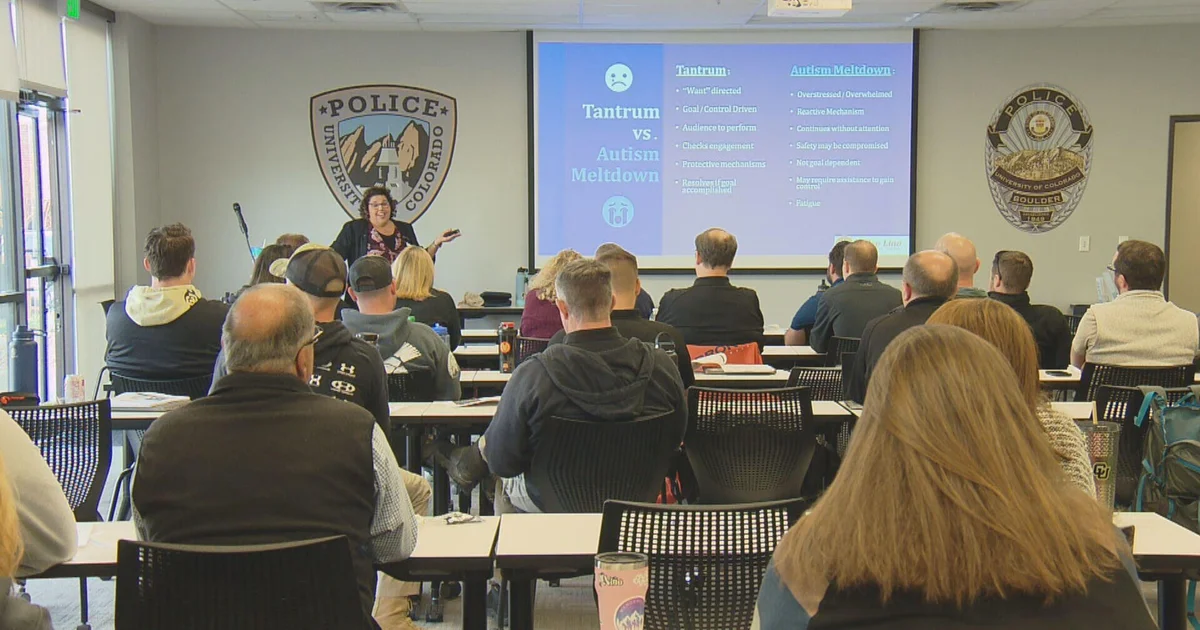

A training program in Colorado aims to improve how police officers and sheriff deputies interact with individuals experiencing mental health challenges or disabilities. Offered for free through the Pulse Line Collaborative, this program has seen varying levels of participation among local law enforcement departments.

The eight-hour training session is funded by a grant that is set to expire at the end of June 2025. Despite its availability at no cost, some police departments have opted out of the training. Ali Thompson, CEO of Pulse Line, highlighted a need for a shift in traditional police training methods. Historically, officers have been taught to issue commands in a sequence: ask, tell, and make. This approach can lead to negative outcomes when dealing with individuals who may not respond as expected due to mental health issues.

Thompson noted that when individuals do not comply with officer requests immediately, officers often resort to physical enforcement, which can escalate situations and lead to charges of resisting arrest or assault. Having a personal connection to the issue, Thompson is a former law enforcement officer and a parent of children with disabilities, including a son with autism who can lose his ability to communicate in stressful situations.

The funding for this training program comes from the Colorado Fines Committee, established after a lawsuit addressing the lengthy wait times for individuals needing evaluations related to their mental health and competency. Colorado has faced significant financial penalties due to these delays, resulting in individuals with mental health and disability issues being held in jails for extended periods.

The state has experienced several tragic incidents involving individuals with mental health challenges, highlighting the urgency for better training. Thompson pointed out that proactive training could prevent such tragedies, asserting that officers often lack the necessary tools for effective communication with individuals facing mental health or developmental challenges.

The Douglas County Sheriff’s Office was the first to request this training after deputies struggled to manage a situation involving an autistic middle school student. Other departments, including those in Boulder County, Loveland, and Arvada, have since participated. However, notable departments like Denver and Aurora have declined the training. Denver initially committed to hosting 40 training sessions but later reduced its participation to just one session, which ultimately could not proceed due to insufficient officer attendance.

Aurora Police Department expressed interest in the training but has yet to commit fully. They reported that officers receive mandatory Crisis Intervention Training and are exploring additional training options. Joe Moylan, an Aurora Police representative, mentioned that scenario-based training occurs regularly, but they may integrate this new training into their existing program.

Boulder County Sheriff’s Deputy Sarah Cox recently applied skills from the training in a real-world situation involving a dispute between a mother and her aggressive autistic teenage son. Cox recognized the signs of distress and adjusted her approach, which ultimately led to the son receiving necessary care at a hospital.

While the training is free, it is not mandated under Colorado’s Peace Officers Standards and Training (POST) requirements, and participating departments face challenges related to lost hours for their officers. Thompson emphasized that the training helps officers improve their skills significantly, revealing that departments involved in the program can better defend their actions in legal situations, as questions about training often arise in lawsuits.

The Pulse Line training program offers an opportunity for police departments to better serve their communities by equipping officers with vital skills for handling sensitive situations involving mental health and disabilities.